San Francisco, September 12, 1976: This is called a switchboard.

San Francisco, September 12, 1976: This is called a switchboard.

In Henrietta, Texas, in the upstairs (outside staircase, on the right) of the building at Bridge and Gilbert, on the corner of the courthouse square, was the phone company before dial phones were available. that was the phone company before the new building was built over by the Methodist Church, and before the time Mac McGilvray ran the phone company. [CLICK HERE TO SEE THAT BUILDING TODAY] In that upper floor were several switchboards, and that’s where the operator(s) were before the advent of dial-phones. You picked up the phone and asked Gladys to connect you to the Watson’s house.

After dial-phones, high school, and heading off to North Texas State University, I learned to operate a switchboard when I worked at Holiday Inn in Denton, and switchboards were still widely in use in the hotel/hospitality industry for inter-room and inside/outside calls for decades after that.

Years earlier, starting back east, the very first answering services had been created when some entrepreneurs obtained AT&T switchboards, and located themselves in a calling area (ie: near the “central office” where calls are switched, serving one particular neighborhood, identified by the prefix of the phone number. In Henrietta, I think it was Evergreen, but I’m not sure I’m remembering correctly, because San Francisco also had Evergreen exchange, north of Golden Gate Park.)

These first answering services worked like this: They had the phone company wire an extension of the business’s phone and the two wires were connected to ONE of the holes in the switchboard. In this way, when the business was closed, the calls were also “ringing” on the small red light beneath that hole. At the back of the console, shown above, you see the red objects which are plugs. You grab the left-side plug of any pair of plugs, shove it into the hole and now your headset (if you’re the operator) is live as you’ve just “answered” the call, like people at home do when they lift the receiver. Now the caller asks for the Watson’s house, or for room 117, and you plug the right-side plug of that pair into the Watson’s plug or room 117’s plug, and flip the small toggle switch in front of that pair of plugs. This rings the target phone at the Watson’s or room 117.

When the Watsons or room 117 answer, you flip the toggle another way, and you are removed from the conversation. You get another red light when the parties hang up.

All answering services around the country used switchboards to provide answering service to businesses right up until 1976 in San Francisco, when one day I got an advertisement falling out of my phone bill. It was for this new feature, “Call Forwarding.”

I was stoned at that moment and picked up the advertisement, and then said to myself. “I could use this to build an answering service, without the need for a switchboard.”

And … that’s what I did. The beginning of Network Answering Service.

A few years later, and 80% of the answering services in San Francisco had transitioned away from switchboards, to call-forwarding and new types of equipment.

That’s how it happened. Thank you, switchboards!

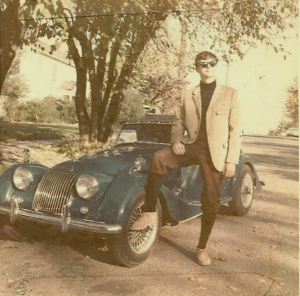

The Morgan Motor Car

North Texas University, Denton, Texas, 1965. Heartbroken, after running off my high-school sweetheart, envious met her new flame, a boisterous trumpet player driving a red MGB.

North Texas University, Denton, Texas, 1965. Heartbroken, after running off my high-school sweetheart, envious met her new flame, a boisterous trumpet player driving a red MGB.

Shortly thereafter when crazy Becky Jarvis said, “You ought to get a Morgan.” I said huh? And then …

I bought a Morgan Motor Car in Dallas from a garage guy named Big John, who imported them and raced them. This one was blue, with tan upholstery and black top. Three thousand dollars.

Built with a wooden frame atop a steel z-frame, whatever that might be. The whole car flexed. Weighted 1400 pounds and had a 1.5 liter engine, hopped-up Ford Cortina with Lotus modifications, Jaguar trannasaurus, ran like hell, whining high-pitched, a redline at 9000. About four inches from the ground. That would be your butt, flying above your asphalt.

The first night, driving it home, in the dark, was terrifying. It was so fast. Seemed like piloting the bolt from a crossbow, rocketing down that dark backwoods highway. Later discovered it had the wrong speedometer; and my highway trip at 65 was really around 90. It did seem sprightly.

The jack arrangement was to insert the jack through a hole in the floor. This hole normally was covered by the rubber floor mat. However, on rainy Dallas days I have seen the puddle splash up through the hole, lifting the floor mat, to spash against the windshield, on the passenger side. Kind of a defroster system.

Paul Miner drew up cartoons of our gang at that time. Mine was ‘Richard, the sports car nut’. It showed me in riding pants, saying “Of course, she won’t start on cold mornings, but at $2999, she can afford to be a little temperamental.”

Paul was right on the money. One of my proudest moments at that time was during an astounding snowstorm. On Dallas freeway and headed back to Denton, I let the air out of the tires down to about 15 pounds. Then, my 1400 pound car could walk up the icy hills where the big sedans just skidded and spun. Got me through. Good thing. That heater. I probably would have died out there.

A year or so later, living in Dallas in an apartment rented from Dunia Bean, which had a swimming pool, driving to work at the Cabana. And a fool oncoming lost it and bent my car. That was the end of the Morgan.

Regarding that swimming pool. It had an underwater light. Have you ever, at night, on LSD, opened your eyes underwater to look at a light? No?

Well, that Morgan was something.

Band of Thieves

Shady Shores community, near Dallas Texas, 1964: Paul H. was the largest roommate, and visiting his girlfriend in Fort Worth, he drove that highway often. A large and quiet guy, when he returned that day, all excited, we knew something was up.

Shady Shores community, near Dallas Texas, 1964: Paul H. was the largest roommate, and visiting his girlfriend in Fort Worth, he drove that highway often. A large and quiet guy, when he returned that day, all excited, we knew something was up.

“What is it?” asked Hardy M., the art student, a rugged fellow of sour demeanor. Paul lowered his voice.

“It’s a boat, with two big Evenrude motors,” he said, “It’s just sitting on a trailor beside the highway!”

My roommates, and myself, instantly became criminals.

“You mean … just sitting there?” asked Pat M. Always affecting calm, always worried.

“Trailer hitch,” Paul said. “I’d have grabbed it but I don’t have a trailor hitch.” On his car, he meant. They all looked at me. My car had a trailor hitch.

“OK,” I said. And so off we drove, to steal a boat.

Along the way, Hardy in the back seat was dozing. Each time he nodded off, Pat jabbed him in the ribs with an elbow. “Stop it!” Hardy said, irritable. Pat told him not to be leaning on him. Hardy said ok, and a short time later, was dozing again.

With the two of them bickering like children, we drove. The day was late, and daylight fading. I’d forgotten a ham in the oven. We found it the next day, much smaller and very salty.

Watching for the boat as we drove, it seemed like we’d never get there. And finally, Paul said that either we’d missed it, or somebody had picked up the boat. So we turned around.

By now, Hardy was deep asleep in the back seat. He woke occasionally, but Pat told him we weren’t there yet. This continued until we were pulling into Shady Shores, where we lived lakeside in a concrete-block house.

About a block from our house was a small copse of wood, and, as it was now full dark, instead of going home, I pulled my car into that tiny wood. In the dark, the nearby houses were invisible from within the trees.

Hardy woke as we exited, but we told him we were going to get the boat, and needed him to stay with the car. Sleepy, he agreed, and promptly fell asleep again. We walked to our house, and stayed up late, talking about our big adventure — failing to steal a boat — and then eventually everybody went to bed.

Hardy, of course, woke up sometime during the evening, but didn’t dare leave the car. He didn’t want to be stranded in an unknown place near Fort Worth.

In the morning, about coffee-time. Hardy came through the door.

“That’s not funny,” he said.

Jerry Lefevre

Marine on St. Croix, Minnesota, May 18, 2017 — Jerry Lefevre was two grades older than me in High School. He bought a Chevrolet. It looked much  like this picture, except that it just wouldn’t do.

like this picture, except that it just wouldn’t do.

Not according to Jerry.

The problem was the red panel. Jerry thought it was not cool.

He had the red panel painted white like the rest of the car. Therefore I cannot now find a picture to show the car. Perhaps it was the only one of it’s kind.

As was, in my eyes, Jerry.

Gravelly voice even as a teen, speaking in short bursts of [Read more…]

The Super Secret Missile Base at College

North Texas State University, Denton Tex 1965as, Fall: Just north of town was a super-secret Nike missile launching facility, and nobody was supposed to know about it. Here’s a picture of it —

The road at the top of the picture is “Locust Street,” or as locals called it “Missile Base Road.” Because how could you not know? I knew, and I was just an undergraduate.

You see, an engineer was brought in because it turns out that the missile pad was actually just a tiny bit too low for proper launching so as to wipe out some foreign city far away. And this guy needed to figure out how to raise is very slightly.

He stayed at the Holiday Inn, where I worked the night shift, and that’s how I know. After all, it was a secret but he told me because I was a trusted motel employee, right?

Then, a couple of days later, he came in to check out, with a huge bag of nickels. They were left-over nickels he explained. He was real happy. Turns out that the thickness of a nickel was exactly the amount they needed to raise the floor.

So he’d gone down to the bank downtown on the square, [Read more…]

Michael Murphy – North Texas Troubador

1308 1/2 W. Hickory Street, Denton Texas, Spring, 1963: The movie ‘Hatari’ was unmemorable, but the Henry Mancini song called ‘Baby Elephant Walk’ had been on the radio for weeks and weeks and weeks.

That warm day, an abundance of visitors from the HobNob to my minuscule apartment somehow drove us all to clamber up onto the flat roof. We also had beer. That may have been part of it.

On the front edge of the flat roof, with our feet dangling two stories above Hickory Street, we lined up to tell stories and watch the students and passers-by across the street on the campus.

Michael Murphy had brought his guitar.

You may remember Murphy from later, because in 1975, along with Linda Ronstadt, John Denver, the Carpenters, Doobie Brothers, and Ozark Mountain Daredevils, his pop single was at the top of the charts with lots of airplay across our great nation. His song was about a horse and a blizzard, and some mountains in Nebraska. The song was called ‘Wildfire.’

(Want to hear it? It’s on this musical video from a tv performance.)

That song haunts me still.

Odd, too, because back on that day when we were all sitting along the edge of the roof, Murphy had earlier come busting into the HobNob, grinning and giggling and just beside himself. He’d just sold his first song, for actual money. He’d made $50. That was a *lot* of money.

For a song!

He’d sold his song to the New Christy Minstrels.

Murphy was a handsome kid then, with a square jaw, blonde hair, an engaging smile and a friendly manner. We didn’t know just how good he was. But he was focused. He was going somewhere. And I guess selling an actual song, for actual money, to an actual known group … well, maybe this was something that consoled him, drove him forward, perhaps he heard fate whispering in his ear, ‘You can do this. You can do this. Just keep on.’

But on that day, as was common, he’d brought his guitar, and after he scrambled to the roof, we passed it up to him, and so, sitting on the roof above the street, he played for us, and we sang snippets of popular songs.

The sun was warm, and we had beer and comraderie. I suppose school officials would have been horrified, but nobody noticed us there despite our catcalls and hooting and laughter.

Down below, an ongoing parade of people walking provided more amusement.

Then a very rotund girl came chugging up the sidewalk. It wasn’t that she was fat, though that was unusual in those days. It was something prissy about the way she walked. She was swinging her shoulders as she came, walking all prissy, and moving right along.

From the guitar, suddenly we heard a tune we all knew. Baby Elephant Walk.

We fell apart, laughing.

And that’s how we’ll remember that day, on the edge of the roof above the street, with friends and laughter in the warm sun, and the Baby Elephant Walk.

Which is Alive? The Singer or the Song?

Medford, Oregon, May 2, 2015 — Now that I live on Siskiyou Boulevard, next door is a sometime fiesta. That is to say, the Latino family next door has the house on the corner, and apparently a never-ending extended family and circle of friends. So often on a Friday evening there is a gathering with Spanish music and beer. And when one of the children has a birthday … oh, my.

So when I returned from an errand this afternoon, and saw an inflatable tent thing in which children can bounce and fly around, I recognized birthday in progress. Sure enough, around dark, headlights and cars arrived, families spilled out into the pools of light, and now as I go to bed there’s a wonderful party going on next door.

It’s summer, and I have the window open beside my bed, so I can enjoy the party almost as well as if I was there. Past my window, in their back yard, children run, and scream, and yell stories, accusations, laughter, curse words, and insults. In other words, they’re having a good time.

You might think this would disturb my sleep, but it doesn’t. Somehow I like it, and despite the startling loudness and excitement, it’s pleasant and soothing.

I drifted off, smiling, and then … [Read more…]

Sponging at the Girl’s Dorm

North Texas State University, Denton Texas, 1962: When several of us lived in a house in Shady Shores on Lake Dallas, there was kind of a ‘girl gang’ who came to visit.

Jan was round and pretty, and she liked Hardy.

Jill was thin, clever, and funny, and I liked her.

Shayna was mature, beautiful, and she liked Paul, who was actually engaged to someone else, though that didn’t seem to interfere much.

They’d all show up at the lake house. We laughed a lot. I remember nights with a bonfire on the beach, a lot of beer. I remember driving to some dive up the road where, again, we drank a lot of beer. I grew sleepy and closed my eyes and pretended to be blind for a while.

“Come on, blind man!” Shayna said, “Stay with us!”

She was Jewish, daughter of a well-to-do Dallas family who owned a milk company. I didn’t know much about being Jewish and asked questions. She said they didn’t believe in the Devil, and so I asked if she would sell me her soul.

She said she would.

So I bought it, for five pieces of silver, writing up the contract on my typewriter, an impressive red IBM selectric inherited from my stepfather’s office.

She took the five dimes and signed the contract. So I have owned Shayna’s soul for many, many years, because I kept the contract safe in my red box of important stuff.

The red box stayed with me through college, Dallas, St. Louis, England, Los Angeles, Texas, and San Francisco. There were a lot of documents in there, transcripts, and government cards, and drawings, and other stuff, including Shayna’s soul.

But this is getting ahead of myself. Back at North Texas, the next year I got a tiny apartment across from the English building, and rarely saw the girl gang. There was always a blitz of study right before Christmas Holiday, and unlike my friends, usually I didn’t go home right away, but rather stayed in my quiet apartment.

The campus was empty and thoughtful, the weather clear and chill. Restful, it was, though I had no money. One night I spent the last of my cash on cigarettes rather than supper, and in the morning I woke up hungry.

Down on the corner in the early morning light, I saw the bread truck parking to deliver to the Hob Nob. As the driver went inside, I crept from the bushes, jumped into the back of the truck, stole a loaf of bread, and ran.

As I glanced behind me I saw Larry Burns, the young man who operated the Hob Nob, standing in the back doorway. He was watching me and laughing. Damn!

Holed up with coffee and bread and cigarettes, pondering starvation, I remembered that, during the holiday vacations, the cafeterias of all the dorms closed, except for one. The same dorm where the girl gang lived.

So I called on them about lunchtime, and discovered that any dorm students stranded on campus over the holiday took meals there in the girls dorm. I walked into the dining room between Jill and Jan. Lunch!

Free lunch! Lots of lunch! Plenty! Free!

The cafeteria ladies, seeing so many unfamiliar faces, just assumed I lived in one of the dorms, and fed me along with everyone else.

I went back every day.

That was the last time I saw the girl gang. Things happened, and you lose track.

And twenty years later, in a flat overlooking Geary Boulevard in San Francisco, where I lived in a small room at the back of Network Answering Service, I found Shayna’s soul stored carefully in the red box.

Through her family’s milk company in Dallas, I located her, married long since and living on the coast north of Los Angeles. I called her.

She didn’t remember that I owned her soul. She hadn’t missed it. We hadn’t much to talk about. Things had changed.

After the phone conversation, since I had her address, I mailed her soul back to her.

It was the least I could do.