A House Not Bought

The flat was built into a garrett beneath the roof, four floors up, on the corner of Lyon and Oak. Our high kitchen windows overlooked Panhandle Park, and each year we’d awake one morning to the sound of thousands of runners passing on the Bay to Breakers race, and each year on another day we’d awake to see the stage of the San Francisco Mime Troupe. From our high windows front and back we could see the high tops of the victorian houses around us. Janice Joplin had lived in the blue house across the street, once upon a time.

From my tiny office, however, the windows opened only to show the roof of the next house, perhaps six feet away. An occasional gull walked the roof. Not much to see.

But in this room I discovered a house.

Adrienne had introduced me to the books of Charles Givens, who suggests that you save 10% of your earnings, and who spelled out for me the virtue of buying a house. I wasn’t so sure about that 10%, but I’d decided to buy a house.

Every day people called my phoneline to buy voicemail, and on this day I was chatting with a guy who’d called to inquire. He’d lived in San Francisco, down in the lower Mission in a rough part of town, but now had another home in Marin county surrounded by pine trees.

When I told him I was looking to buy a house, he suggested that I might take over the payments on his San Francisco house, which was just about to be foreclosed. I said good idea, and he mailed me a key to go see it.

In case you don’t know, houses in San Francisco are very, very expensive. Even the smallest ones back then cost a quarter of a million dollars, and during the high interest rates of the 1980’s, for a self-employed person, monthly mortgage payments would generally exceed $2000. I’d probably be able to handle that, but the down payment would exceed $60,000, and I’d never, ever had that much cash at one time.

This house had payments already made, so its cost was $130,000. I was interested. The house was run down, slightly set back as if hiding narrowly between two other homes. Behind a high fence, it was two stories, dingy and cheap throughout. It would take a lot of work. But with no downpayment other than the back payments, and a monthly payment of $1400, it was a good opportunity. My contractor friend Pat looked at it. He regularly bought and fixed up homes. He said it was a good deal.

I raised the back-payments money from my friend Dennis, signed an agreement with the fellow who owned it, and took a check to the bank. Now in less than a week I owned a house.

Proudly, I took Adrienne to see our new house.

She became silent when we arrived in our new neighborhood, and was frowning on our new street. Her eyes widened as we parked outside. Once inside, she seemed stupified, and then burst into angry tears.

She hated it. How could I have bought such an ugly place? My pride contracted … became concern … evaporated. She said she would never live in such a place. It was ugly. It wasn’t a nice house!

I was in a quandry. The money had already been paid to a bank. Too late, I realized I’d made a fundamental error in not consulting her. I’d thought she’d be as delighted as I was. It was to be a surprise, and the surprise had gone bad.

Oddly enough, the next day, the bank sent back my check, uncashed, for the back payments. They said that the payment had to be a cashier’s check. I gave the money back to Dennis, and phoned my regrets to the house’s owner.

Today, that house would be worth perhaps $400,000, perhaps more. It would have been a stupendously good investment. But I don’t have that house. In fact, I have no house at all.

But I do have Adrienne. She’s my million-dollar baby.

Haiku the Blog

St. Peter loses

the keys to heaven; God to

call for a locksmith.

~dayla_starr at 05:37:4

This Newfangled Daylight-Savings Time

Dallas, Texas, Spring 1966: Living in Dunia Bean’s apartment on Gillespie street, I worked at the Cabana Hotel. The Cabana is a clone of Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, complete with over-sized statues of Venus, David, and the rest of the crew. Inside, a vast two-story lobby with greenish marble floor and a round sunken area with sofas enough for a football team.

Dallas, Texas, Spring 1966: Living in Dunia Bean’s apartment on Gillespie street, I worked at the Cabana Hotel. The Cabana is a clone of Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, complete with over-sized statues of Venus, David, and the rest of the crew. Inside, a vast two-story lobby with greenish marble floor and a round sunken area with sofas enough for a football team.

Overlooking this magnificance, our front desk where I worked with Dick and Earl, dignified alcoholics. Dick taught me how to get big tips at crowded times, and Earl as a young actor fought swords with Errol Flynn in the movie Captain Blood. That was a while back.

But this was in the spring, and for the first time since the war, Texas was going to have Daylight Savings Time. We were all abuzz.

Paul the Bellman was a portly fellow, balding and gabby. He made big tips because he knew about health food and horoscopes. This was years before such things were popular. His most popular health food remedy was honey and vinegar; he’d recommend it for almost anything.

On the way to the elevators with the guests, he’d ask about their birth-date and provide predictions and prescriptions all the way to the room. Then I suppose it just seemed wrong, to the guest, to tip miserly to the fellow who’d taken such an interest in their fortunes and their health.

Paul the Bellman was very opinionated, and also had an annoying habit of slapping his hand down on the bellman’s marble-topped desk when he was about to speak. This made a loud pop. I think it was his version of banging the Judge’s gavel before pronouncing sentence.

So, while we were all discussing this radical new change, Daylight Savings Time, and how we would set our clocks before we went to bed, Paul returned to the bell desk.

Slap! went his open palm on the marble desk. “Well,” he said, “I know what I’m going to do.” We all stopped talking. He continued. “I’m going to set my clock for one a.m., and then I’m going to wake up, and set it ahead to two a.m.”

We all stared in incomprehension. “Why, Paul?” I asked.

“That way,” he crowed, “I won’t lose an hour’s sleep!”

I grinned. “But Paul,” I said, “If you’re awake when you move it forward, won’t you lose an hour’s wake?”

He pondered this. “Naw,” he said, “You can’t lose an hour’s wake.” We all nodded.

Slap! went his palm on the desk. He scowled. “But those guys better watch out,” he said.

We looked at each other. He went on.

“Because when they’re changing the time, they’re messing with the sun,” he said. “And they’d better not go messing with the sun!”

Thus came Daylight Savings Time to Texas.

Eddy Frank

Lulu Johnson Elementary School, Henrietta, Texas, 1953: In the third grade, Eddy Frank was a big hit with Susan J. For reasons I could not comprehend, she favored him above other, more attractive boys, such as, for example, myself.

Susan had invented a wonderful game, and Eddy Frank knew just how to play it.

Susan had two little girl accomplices, and, in cahoots, the three of them would sneak up on Eddy Frank, who pretended he didn’t notice. When they jumped him, the two would grab his arms, and he’d wail, “Oh, noooo!”

Meanwhile, Susan J. stepped around to face him, and then, grasping her skirt, she’d pull it high, exposing her brown belly and girlish drawers. Eddy’s eyes bugged, as he feebly struggled.

“Oh, no!” he’d cry out. “Don’t make me look! Don’t make me look!”

Oh, the anguish of it! His wailing cry, the pathos! The boy had the touch. I burned with envy, but never found a way to insinuate myself into the game. I mean, how do you say, “Don’t make me look, too!”

Eddy Frank’s unique brand of resistance made him irresistible. But Eddy Frank wasn’t just skillful with the girls.

That year, a new kid showed up. A skinny, burr-headed boy named Jimmy B. He was the solemn-faced, thin and wiry kind of kid. He seemed tough, and said little.

At the first recess, we gamboled in the fresh September air on the north side of the school. But not Eddy Frank and the new kid. Eddy Frank and Jimmy B. were circling each other, warily. Not a word was spoken. Suddenly, Eddy Frank jumped the new guy. It was a grand fight. Rolling over and other, dirt and pebbles flying, wild fists flailing, tearing shirts, with lots of grunts and growling. They were just wild.

We enjoyed this spectacle until Ms. Gilbert and Ms. Stine pulled them apart. It was clear that Eddy Frank had started the fight, and it seemed out of the blue. That was part of the wonder.

Ms. Gilbert shook Eddy Frank’s arm. “Why did you do that?” she hissed. Eddy Frank glowered at Jimmy, then slowly answered.

“I didn’t like his looks.”

Cousin Bruce in North Beach

Grant and Green, San Francisco, 1974: While I was living in the apartment from hell in North Beach, I called my cousin Bruce again.

Grant and Green, San Francisco, 1974: While I was living in the apartment from hell in North Beach, I called my cousin Bruce again.

He said that he knew that apartment building, because he’d once been abducted there.

Bruce was several years younger than I, and was mostly seen during family get-togethers at the farm. He’d been a young active boy with red hair and a mischevious nature, alternating between brashness and uncertainty, with just a dash of yearning.

He told me years later that, at the end of a visit, when his family was ready to leave, he would slide a red rubber band around the knob on the bannister of the pine staircase in the hall, so that he was leaving something of himself in that place. And when they returned in a year or so, he’d run to the house, to see if the rubber band was still there.

Sometimes it was; sometimes it wasn’t.

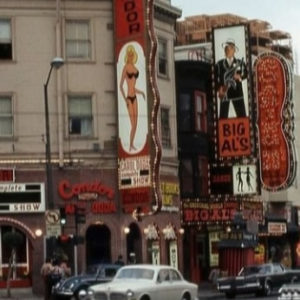

In college, he’d become fascinated by video, and seeking his video fortune, he arrived in San Francisco, and spent the first night at a cheesy hotel on the corner of Columbus and Grant. Perhaps you’ll recognize the spot as a strip joint called the Condor Club, where the famous Carol Doda put on floor shows. It was in this club that her piano killed a man.

Here’s what happened: A waitress had picked up a boyfriend for the evening, and they stayed late, after the bar closed. Carol Doda had a white piano which descended from the ceiling, as part of her act The drunken pair wondered what it would be like to make it on the famous piano, and while engaged in exercises there, triggered the lever which sent the piano returning to the ceiling.

The two were pinned in missionary position when it reached the ceiling; the fellow had a heart attack and died. The waitress, trapped beneath the dead man, was quite sober by the time janitors arrived in the morning light.

At the corner of the building was a two-story sign with a huge plastic Carol Doda posing, in black plastic panties and bra. On the upper floors we find the cheesy hotel, and Bruce’s window was five feet from this gargantuan bra. Being drunk enough, he leaned out to pull that bra off Carol Doda. It wouldn’t come free, though he broke off the strap, and for years after I felt a certain surge of pride whenever visiting North Beach. Our family had left its mark.

Bruce was looking for an apartment the next day, when suddenly an older guy, grizzly with a dirty grey beard, grabbed Bruce’s arm, and shoved Brude through the doorway of my apartment building. The fellow was much larger and stronger than Bruce. Grim-faced, the man said nothing, and dragged Bruce up the stairs. Bruce figured he was about to be killed. So he stumbled to pull the guy’s arm, then straightened, then launched himself straight backwards into the air. The fellow had to let go or fall down the stairs.

Bruce dropped six or seven feet to the landing, ran out, ran away up the street, moved to Berkeley, and never learned what it was about.

But of course, like the curious couple in the bar, there are some things a person just doesn’t need to know.

Carnaby Street

His name really wasn’t Ron David, but when I met him in Dallas, he worked as D.J. on the local rock station, which insisted that each D.J. be named David. So Ron McCoy became Ron David McCoy. I visited his control room while he spun chatter and platters with a rapid-fire style I found amazing. Good-humored, a skinny guy with Elvis hair, and a baby-doll wife, a real looker.

The McCoys were fun, too. But I was shivering.

The wind whistled up Carnaby Street, and I’d come with no coat. The girls were bundled up, and Ron David had a long trench coat which reminded me of one I’d bought at Midwestern University, years ago, charcoal-black with a subtle gold-brown check, lined, with deep pockets. I’d thought it made me look very much like Holden Caulfield.

I’d got it muddied almost at once, and thought it ruined, but took it to Ray Moore’s Cleaners in Henrietta. Ray had dry cleaned for my family all my life. Back came the trench coat, perfect. You’d think it new except for the tiny tag of cloth pinned inside with my name. I think about all the clothes over all those years, and wonder how many tiny tags Ray had made for my family, for all the families in our town. Somewhere today, in a back closet, in a junk yard, I imagine an old garment long forgotten, still with the faded tag of cloth fluttering to tell the world my name.

Me and that trench coat had travelled many miles. I wished I had it now, because I was chilling to the bone. I looked enviously at Ron David. I tried to walk faster.

The three of them were laughing and telling stories, but I was trying to remember. My trench coat should be in the house in East Grinstead, but I didn’t think so. I knew I’d brought it from Texas to St. Louis because I remember Sam putting me up for a few days, and he’d borrowed it. And then I’d packed it up again and moved to the unheated house trailer off the end of the jet runway. I’d not worn it that winter: too cold for a trench coat.

But I couldn’t remember packing it for England. Maybe I’d finally lost it. Then I had a thought, and turned to Ron.

“That’s a nice coat,” I said.

“Thanks,” he said, looking down at it.

“Where did you get it?” I asked.

“Oh, I borrowed it from Sam,” he said. Aha!

“You know, Ron,” I said, “That’s my coat.”

“What are you talking about?” He stared. I nodded.

“I left it with Sam for safe-keeping,” I said, “You’re wearing my coat.” He looked indignant.

“I don’t see your name on it!” he said. Wrong answer.

“Open it up,” I said. He did.

Thank you, Ray Moore. There, near the hem, a tiny piece of cloth fluttered.

So nice to have my coat back! So nice of Ron David to bring it to me, all the way from St. Louis, and just when I needed it, too. So nice and warm, there on Carnaby street.

A Photograph of the Future

Denton, Texas, Winter 1964: Living in my one-room cool apartment at 1308 1/2 West Hickory, across from the English Building, somewhere, somehow I came across a book of photographs about San Francisco.

Taken in the Beatnik heyday, late 50’s, the photos show Chinese children playing hide-and-seek up and down the narrow, hilly streets, show the intellectuals drinking espresso in stark coffeehouses, show women dressed as models shopping grandly, and much more.

Taken in the Beatnik heyday, late 50’s, the photos show Chinese children playing hide-and-seek up and down the narrow, hilly streets, show the intellectuals drinking espresso in stark coffeehouses, show women dressed as models shopping grandly, and much more.

Lefevre and I had visited San Francisco while returning from the Seattle World’s Fair in Summer two years ago when I graduated high school. My senior year in study hall, I’d read about the fair in Life Magazine. Then, in San Francisco, I’d become enamored of the beautiful Victorians, the views, the exotic sights of Chinatown and Little Italy, oops I mean North Beach. So this photograph book reminds me of the strangeness and the beauty.

And, oddly, one of the photographs shows my apartment, where I will live ten years from now.

And, oddly, one of the photographs shows my apartment, where I will live ten years from now.

Ten years from now, I’ll be rooming with Pat Q. the photographer off Clement street. As his marriage grows near, one day he will tell me that I’ll need to find another place to live. When I complain, he will say, “It was always there.”

He will be meaning that it was always obvious that someday he’d marry Andrea and that I’d have to go. So accept this I will, and I’ll begin to search the paper for apartments. This will be in the days of writing my novel of Texas, when I am beginning to study the Tarot.

I took up the Tarot when living in an eyrie room atop Mrs. Douglas’s house in view of the ocean. I meant it to provide a way to generate plots for stories and novels. I found much more. When living with Pat Q., I started studying magic and Tarot. I became disgusted one day, and said, “If there is anything to this Tarot, then let the next card be the Page of Cups!” I cut the cards.

Yup. Page of Cup.

Whooah! So, given my mystical frame of mind, perhaps it’s not surprising that one day, I say, “I’m going out right now and find my apartment!” I walk from the house, and catch the first bus I find, which takes me to North Beach. From the bus I walk up Grant street, and there, on a window above the Hawaiian Bar on the corner, the red and white sign says, “Apartment for Rent.”

Quickly, I ran back down the hill to City Lights Bookstore, where I grabbed a copy of the I Ching, and picked a page at random. “Supreme Success!” is the name of the Hexigram.

I rented the apartment immediately, from the lady manager of the Hawaiian Bar, and moved in. The apartment was a vast success in one way, because my neighbor was giving up his kitty whom he called Gish. He said he had two cats and only needed one, and he was taking Gish to the Humane Society.

At the time, I believed they killed the cats there. Later I discovered that most cats at the San Francisco Humane Society get placed with new homes, but at the time I thought it was a death sentence. I’d not had a cat because I thought life in an apartment wasn’t much compared to wandering free.

But I figured life in an apartment would be better than being killed, so I took young Gish and named her Rosie the Cat, and we spent the rest of her life together, but that’s another story.

As regards living in the apartment, Rosie liked it because there was a mouse to chase, and cockroaches to eat. There was also plenty of late-night Hawaiian music from the apartment, and a number of other unique features. In fact, thinky back, it was The Apartment From Hell.

But getting back to this photograph book in my college years. In this one photograph are shown a bunch of bums drinking wine, standing around the street sign for Grant and Green. In the upper left you see the bay window of the apartment on the next floor.

This was to be my window. From that window, had I been there for the photo, I could have leaned out and, with a yardstick, smacked the bums on the head.

Too bad I wasn’t there, until ten years later.

Though oddly, when I arrived ten years later, the bums were still there.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- …

- 55

- Next Page »